Ask Me Anything

Welcome to my “Ask Me Anything” Series! I started this series a few years ago on social media, when I noticed what wonderful questions my followers were asking about my writing life. It surprised me, when I began to answer some of these questions, how much I loved reflecting on various parts of my career, research process, writing routine, and sources of inspiration. Over time, however, the Ask Me Anything posts have gotten buried in my feed. A friend suggested I provide a special home for all the questions and answers in a corner of my website so that people can continue referencing them easily. And so here you are.

I’ve restarted the series on social media, and though my schedule will be too harried at times for me to be super-consistent with updates, when I have time, I really love to feed this ongoing conversation.

And if you’ve ever wondered about how writers work, find inspiration or research ideas…or wanted to know something specific about my books, characters, process, or what have you—now’s your chance. I’m at your service…so fire away your questions on my Contact page.

The Writing Life

When did you know you wanted to be a writer?

I started to write poetry when I was 8 or 9, gravitating to words to express what I couldn’t or didn’t know how to say out loud. Like reading, writing was an anchor point. A net that seemed perfectly shaped to catch me. I WAS a writer from the earliest, but didn’t know I could BE a writer—be audacious enough to want that for myself—until I stumbled into my first creative writing class at 23 or 24. I was taking a lot of science classes, thinking I’d be a biology teacher. A nurse. A geologist. My indecision was intensified because it took a lot just to get by. I moved often, worked minimum wage jobs full-time AND tried to be a student. It took 7 years to get my degree, after dropping out twice because I couldn’t keep my grades up. The poetry class felt like a lark. An impractical way to spend my electives and time. I loved it. The professor challenged me to read contemporary poetry. A lot of it. The more I read, the more I wrote. The more I wrote, the more I knew what was possible in the world of language, particularly metaphor. My mind blew wide open. The following semester, I took a second (deeply impractical!) writing class. My professor asked if I’d ever considered getting an MFA in poetry. I didn’t know what that was. That you could study to be a writer? Where had that door been all my life? It didn’t matter. Once I could see it, I dared myself to walk through it. Decades later, I’m still doing just that. Choosing the writing life, again and again. Re-committing to the work. To the difficulty. The uncertainty. All of it. Sometimes—and this is what I really want to say—we don’t know how big the world is, or what we can dare to want for ourselves. Sometimes we’ve never been encouraged to dream widely, in the direction of our gifts. In the many years I taught writing—and still to this day when I meet an aspiring writer with significant talent—it gives me such joy to be able to tell them they ARE a writer. Not because I have any particular authority as a gatekeeper, but because I know how transformative it can be to hear that yes, to know that the door is there, and open.

When you wrote your first book manuscript, was it difficult for you to let someone read it?

I went to graduate school to study poetry, but whenever I would talk about my background with the other writers in my program, they always said, “A childhood in foster care? You should write a memoir.” I was intrigued, but overwhelmed by the idea. After all, I was a poet. I wrote terse and deliberately obscure lyric poems. A memoir would require sentences, chapters, SCENES. Still, the idea drew on my imagination more than it frightened me. I was always writing about my childhood in my poems in a veiled way. This would be a direct opportunity to release the stories that were still with me. To let them out of the rubbed magic lamp like a legion of possible genies. One of the fiction writers in the MFA program had started to circulate a list of New York literary agents. After I’d written what I thought might be the first two chapters of my memoir, I drank two glasses of wine fast on a Friday evening, just before 5 o’ clock, and cold called the first name on the list, saying, “Hi, my name is Paula McLain. I’m an MFA student at the University of Michigan, writing a memoir about growing up in foster care in California. If you’re interested, give me a call.” I’m not sure where I got the chutzpah to do such a thing. It might have been a kind of dare to myself. I more than expected to be ignored, and yet first thing Monday morning, the agent called back. “Sounds interesting,” she said. “Do you have a draft to share?” “Yes,” I answered before I could lose my nerve. “I’m just tweaking it.” The fib was another dare. Here was an agent who was offering to read my book if only I could muster the courage to write it. That possibility helped me more than I can adequately explain. I grew bolder. I grew determined. I wrote that book.

How did you get your publishing contract?

The long and short answer is through a literary agent, which is absolutely essential, no matter what anyone tells you, as a way to make contact with publishers. I found my first agent in graduate school. I was studying poetry at The University of Michigan, but had begun a few very rough chapters of a memoir about my childhood spent in foster care. A list of New York agents was being circulated by some of the students in the fiction program. I got a hold of it one day, and for some reason decided to act more boldly on my behalf than I actually felt. I had two glasses of wine late on a Friday afternoon and cold called the first name on the list, Leigh Feldman (who was then at Darhansoff, Verrill and had brokered deals for Memoirs of a Geisha (1997) and Cold Mountain (1997). I left a message on her voicemail saying who I was, what the project was, and that if she was interested, she should give me a call! I had no idea at the time that this was not how things are done. But rather surprisingly, she called me back on Monday. “Your project sounds interesting,” she said. “Do you have a draft to share?” “Sure,” I found myself inventing on the spot. (I barely had two chapters, and they were incredibly rough.) “I’m just tweaking it.” It’s hilarious to me now that any of this transpired—but I’ll tell you this. Knowing that there was someone out there who had agreed to read my book if I had the courage to write it made all the difference. In a way, I dared myself by making that call. I raised the stakes and then made good on the bet by finishing the book the next year. Was it easy to write? Not in the least, but for me, clearing that first hurdle and knowing whom I was initially writing for helped me finish that draft, and then the next, and the next. Leigh sold the book to Little, Brown, and Like Family was published in 2003. Leigh and I amicably parted ways shortly thereafter, over creative differences, and I was lucky enough to find my forever agent, Julie Barer of The Book Group. That’s another story—a good one—for another day😊😊

How did you and your agent Julie Barer find each other?

It seems like a million years ago when my memoir Like Family (2003) was acquired by Emily Takoudes for Little, Brown. Emily was about twelve at the time, I think (LOL) and my book was her first official acquisition. You could say we grew up together. As fate would have it, she left Little, Brown a few months before the book’s publication to take a new job, which was rather devastating. Here I was, writing about abandonment, and then the book itself was orphaned—or so it felt. Like Family didn’t sell well, which added to my grief, but I rolled up my sleeves and began working on a first novel. Later, when my then agent Leigh Feldman submitted the book, we struck out. No one wanted it, and we also couldn’t agree on edits. We decided to part ways but I had no idea how to search for another agent, and had all but lost faith in the novel and my publishing career. On a whim, I contacted Emily Takoudes to see if she had any agents to recommend. The name she passed on was Julie’s. I still remember the first time we talked on the phone after I submitted the manuscript of the novel I’d been working on for years, and which was still a mess. “Your writing is so lyrical and evocative,” she said. “I feel I’m there. I can smell the baby oil. I can hear the cicadas in the trees.” My heart thrummed with hope. Then she said, “You know something has to happen in a novel, though, right?” !! That something she was referring to was a plot. 😉 After a good deal of humility and another year of toiling away, Julie helped me find that plot, and then submitted the book again. As a funny sidebar, which I like to think of as the universe clearing its throat, Emily was one of those editors, and she came in with a pre-empt offer. That book became A Ticket to Ride, in 2008. If there’s a moral to this story, it’s that we never know what’s coming for us. We can’t see the pattern—particularly in the midst of disappointment—or even guess at the diamonds that lay ahead on the path. Julie and I have been together now for five books over almost fifteen years. I like to think we’re just getting started.

Are your morning pages stream-of-consciousness journaling about whatever is going on in your life or specific to the project you’re working on?

I take Julia Cameron at her word when she says the morning pages can be anything at all, and that there is no wrong way to do them. There is something about writing longhand that helps the mind loosen up a little, and find a meditative state, uncensored and utterly willing to let whatever comes up to simply be there, okay as it is without needing to tinker or intervene—or “write.” Shape. Because I’m just coming out of sleep when I do the pages, I often find myself spilling out my dreams, the symbols and characters and recurring imagery that comes up. I also find myself unpacking the stuff that’s swimming in my consciousness, bits of conversation, things I’ve noticed from the previous days or weeks that I’ve continued to think about. In this way, the things that rise to the surface and continue to rise, DO find their way into my novels. My most recent novel, WHEN THE STARS GO DARK (2021), which will be out in April is full of these bits of my life that have “stuck” for whatever reason, and been collected in the net of the morning pages. For me, that’s what’s most interesting about the pages… that they’re a place for me to notice what I’m noticing, and to see what I’m paying attention to, what draws and continues to draw my interest. The way a dowsing rod will lead you to water if you surrender and let it take you there.

Do you write about real life experiences?

The long and short answer to this question is a resounding YES. For the past ten years I’ve been tracing the lives of some of history’s most fascinating women from the inside out, inhabiting their lives and voices in as intimate a way as possible. We are historical beings, after all. We live within time and carry our pasts with us. I find that fascinating.

My latest book, WHEN THE STARS GO DARK (2021), which will be out next month on April 13, is a suspense novel rather than historical, and yet this fascination with real-life crept in anyway. When I was steeping myself in research, I was eerily surprised to learn that there were a string of abductions of young women in the same time period (1993) and geographical area (Northern California) as my novel – most notably 12-year old Polly Klaas, who was kidnapped at knifepoint from her bedroom in Petaluma during a slumber party while her two best friends watched. It became one of the largest and most publicized manhunts in California’s history, and yet more often such disappearances aren’t national news; many aren’t even reported. I wanted to write about that—about how everyone wants—and needs—to be looked for. And as I did so, many of my own early difficult experiences as a kid growing up in foster care sifted into my story, as did my ongoing fascination with intimate violence, trauma and healing, and the complex, magnetic relationship between predators and their victims. There is real life, and then there is real life. Our human story, which will always, always call to me.

Do you ever think of something and then say to yourself, I can’t write that, it’s too extreme?

Yes, I have those thoughts all the time. And I do everything in my power to ignore them. Because those too bold, too extreme, too out-there bursts of inspiration…whether they’re lines of dialogue, moments of description, or ideas for a novel that feels dramatically different…what if they’re exactly the direction I need to be going in order to grow my work? And what if by dismissing them, I’m actually just trying to protect myself from taking a risk and possibly failing or making a fool out of myself, or getting it “wrong.”

Creativity and playing it safe are not compatible. Those left-field ideas might be a little scary to pursue, but that tension, that terrain is what novelist and screenwriter Steven Pressfield calls “The War of Art.” According to Pressfield, there is an inheriting creative spirit that lives within each of us—our highest self, calling us forward to live out our destiny—and an opposing force, which also lives within us. This he calls, “The Resistance,” and is basically anything that keeps us from doing our best work: self-doubt, procrastination, writer’s block, busyness, distractedness, impatience, jealousy, addiction, and maybe even those reasonable-seeming voices that say, “Maybe this idea is too extreme??”

There’s one way to find out 😉

Is your writing a process or a love affair?

Not long ago, in an event with my agent Julie Barer, I was trying to explain to her and the virtual audience that my very favorite feeling of all is being in flow with my work. “How do you get there?” she asked. “Devotion,” I answered without thinking. “I pour words and time and energy and hope and passion and more words into the book. I love it, and keep on loving it, giving it everything I have. And eventually, at some magic point, I can feel it starting to love me back.”

Though my reasoning had slipped out, unscripted, I also knew instinctively that I’d hit on something true. For me, each book does feel like a love affair that deepens along the way, expanding on both sides, becoming more and more rich, rewarding, and intimate over time. Trust is built, little by little. Vulnerability is required. Showing up, no matter what. My attachment to the book becomes a marriage. A binding of souls.

There have been times in my personal life when I haven’t felt great about my track record in the realm of romance. But no one can doubt my commitment to my work, the risks I’ve taken to choose the creative life, and keep choosing it, no matter the costs and obstacles. Along with my children and my sisters, it is the greatest intimate relationship of my life.

There are tests to weather, of course—as with all substantial loves. I’m being tested now, in fact. My latest book has launched. I’ll be doing events through the summer and continuing to talk about it—and care about it. But if the shape of a novel is wave, I’ve ridden this one for three years, from initial inspiration to right now, where I’m standing on the beach, surrounded by softly glittering foam. It’s time to begin something new. To face the blank page, metaphorically and literally. It’s a scary place to stand, knowing that as soon as I step out of the shallows and into deep water, I’ll have to surrender completely again. Be taken over. Pour absolutely everything I have into the work–again. This moment never gets easier, somehow. Never stops demanding faith and audacity. Humility. A touch of recklessness. And love, of course. Always love.

Process, Research and Inspiration

What is your writing routine?

While I don’t follow a rigid writing routine beyond trying to write a thousand words a day, and keeping my butt in the chair until I do, I often turn to Julia Cameron’s morning pages from THE ARTIST’S WAY (1992) (which every single person, ARTIST OR NO, ought to read). The morning pages are three longhand, stream-of-consciousness pages that one writes first thing in the morning, every single morning. They’re a meditation of sorts. The point of them is to get all of that gunk out of your head so that it’s clear for the real creative work that takes place afterward. They are also, at least for me, a sign of devotion, of continuing to show up, no matter what comes. I’ve done morning pages on and off for years…but when I’m beginning a book, as I am now (!!!) they are particularly useful to be in the right frame of mind. Generative and expansive, they keep pressing me onward, even in the midst of so much concern about the world. My writing is my anchor point, the way I stay hopeful and in the present. What about you? And have you done THE ARTIST’S WAY?

Do you fully develop characters and a storyline before you start writing a new book? How much do they change as you go?

A writer friend recently told me about another writer who sits in a dark room every evening and thinks/dreams/plots her next day’s writing, priming her subconscious to do its work while she sleeps. Hemingway believed in the opposite. He would stop writing before he’d depleted his energy, while he had a very clear sense of what should come next in the story, and then deliberately NOT think about his book at all until it was in front of him again. Though this question is really about my strategy after the initial inspiration, my process at the micro and macro level of a book are the same—which is to let whatever imagination actually is (I have no idea, of course, and prefer to let the mystery stand) drive the bus, while I remain a game passenger, curious but also half asleep, lulled by the rhythm of the road. What I’m hoping for, always, is to get lost in the process. To write faster than I can think, so that the creative part of my brain takes over. And my heart, of course. My soul. Any book idea or storyline that my rational mind could plot or plan wouldn’t ultimately be very interesting to me, or very surprising. All of the revelations along the way, big and small, are what keep me here, devoted to the work and sort of in awe, ultimately, not about what I’m doing, but about what art IS. Where the energies of making and inventing come from, and why they move us more deeply into the world.

Do you write in linear fashion—the beginning is always the beginning? Or do you sometimes jump around to other parts of the novel?

Because I don’t use notecards or an outline, once I dig into a new novel, I generally write chronologically through the story. Or what I THINK is the story. The other day, I was talking with a writer friend about how we both slave and slave over beginnings—OBSESSIVELY writing and rewriting—only to discover, several drafts in, that it’s not the beginning at all, but rather a paragraph or a single line somewhere in the middle of it all. It can be so frustrating to think of all that time and effort being wasted, but here’s the thing: We can’t ever glimpse the finished thing before we’ve built it, stone by stone. The process is mysterious, and requires surrender, particularly for those of us who are allergic to not feeling in control! As a sideline (sort of), at the beginning of the year, I got myself a new writing toy in hopes of limiting the amount of editing I do before I have built up enough pages to know what I’m actually writing. It’s essentially just a word processor that shows me only a few lines of text at a time. No cutting and pasting, and no access to the internet. Plus, it’s cute😉 For the moment, I’m liking it, but old habits die hard. Would love to hear some of the *tricks* some of you use to stay focused, and also to access the freer and more creative parts of your mind as you work.

What does a typical workday look like for you?

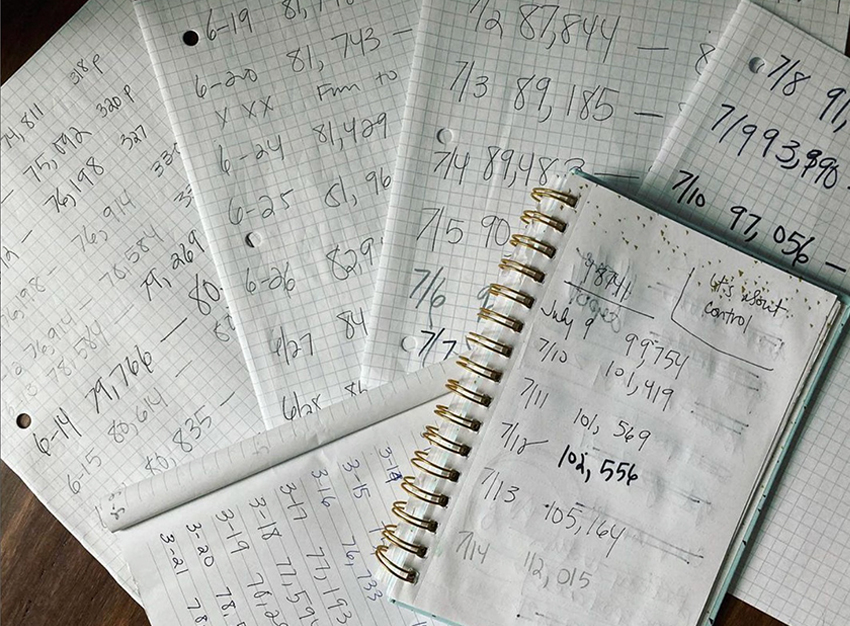

When I’m writing, I’m typically at my desk 5-7 hours a day, 5-7 days a week, and shooting for 1000 new words a day. Ernest Hemingway kept track of his word count each day on little scraps of paper, and I do a version of the same. I’m pretty superstitious about it at this point, and have a habit of saving the notebook pages, receipts or paper napkins I’ve done my accounting on and keeping them with the printed drafts of the manuscripts. It’s particularly important for me to be hardcore with my routine and not let up or falter in the early stages of a book, when I’m trying to generate enough pages to know if I’m onto something “real” or not, and when devotion seems the one thing I can control. Inspiration is wily and mercurial, but I can show up, day after day, and prove my commitment. When I’m stuck, I’ll often go for a walk or make tea, or both—but try not to make calls or clean or play with my phone or do anything else that will break the flow.

Do you do all of your research before writing or do you follow the muse and research as you go?

I love the research process—love what I discover along the way that can totally surprise me, or even dramatically change the course of a book. Many writers I know spend years digging into research before beginning to write, trying to get that solid road map in place 🗺 For me, almost as soon as I’ve had the lightning strike of the idea, and feel I’m onto something, I let the energy and enthusiasm of the initial inspiration drive the drafting process while I do research simultaneously, racing to keep up with myself. What I have is a direction more than a map, then, at the outset, and heat, a burning curiosity to know more. When I reach a place where I absolutely must have facts or the right details to flesh out a scene, I’ll stop everything to learn about bullfighting, for instance, or trench warfare, or racehorse training, or the history of absinthe, and funnel all that in as I go. Is this the most efficient way to write a book that’s heavily reliant on research? Most likely not! But I strongly believe that whatever I learn through research, be it meticulous or organic, or anywhere along the continuum, there always comes a time when I have to launch away from anything like a net or a map or a handrail and rely on my imagination—and my courage—to follow the story where it needs to go 👣

Does your topic find you, or do you find it?

Ninety-nine percent of the time my subject finds me, and for that other one percent, the writing never gels. Here’s the thing, the subconscious is always smarter and more interesting than the rational mind. And it’s always awake. Where the subconscious tips its hand is in dreams–yes–and in obsessions. What we continually find ourselves drawn toand inspired by. What wakes us up at night and keeps us wondering about. If you follow those arrows, they will always lead you to a rich place. Lead you “home.”

Hope this helps. Happy writing!!

Oh, and I’m going to answer a bonus question from Jennifer Anton because it made me smile. “Truth, if you had your chance, would you have gone out with Hem?” Ha. For sure!! Now, I wouldn’t have married him, but that wasn’t the question 😉

I love hearing from you, dear readers! I look forward to your questions and comments each week🌸 Keep ‘em coming👌🏻

Where/How did you research Hemingway’s life?

I often call myself an accidental aficionado of Hemingway, because my interest in him grew out of writing The Paris Wife (2011), and later Love and Ruin (2018), rather than being the thing that lead me to those books. The launching off place for my research was Hemingway’s memoir, A Moveable Feast (1964). From there, I steeped myself in his fiction, and by now have read pretty much everything. Favorites are: In Our Time (1924), The Sun Also Rises (1926), A Farewell to Arms (1929), For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940), The Garden of Eden (1986), and The Snows of Kilimanjaro (1936). I’ve read a ton of biography—by Carlos Baker, Michael Reynolds, Denis Brian, A.E. Hotchner, and Bernice Kert, with a particular fondness for Paul Hendrickson’s Hemingway’s Boat (2011), which is so beautifully written, and a wonderful place to start if you’re interested in his life. Hemingway’s letters are incredibly revealing, and one of the best glimpses into the man, I believe. They’re being published one volume at a time by Cambridge University Press, and edited by the incredible Sandra Spanier. Much of his correspondence and all of his work in manuscript form is held in the Ernest Hemingway Collection at the John F. Kennedy Library in Boston, which I’ve visited by permission, and found really important in my early research. Finally, I’ve been to many of his places, trying to get closer: Paris and Pamplona, Oak Park and Key West and Kansas City, Horton Bay, Toronto, Sun Valley, Cuba. I’ve stood in front of the bed where he was born, and stretched out on his gravestone in Ketchum, slightly tipsy, looking up at the stars, and telling him, “Thank you.” More than any other question, I’m asked if I’ll write about the other wives, about Mary and/or Pauline. I know better than to say “never” to anything, and yet it would surprise me very much if I found myself delving into either of their voices, or picking up more of Hemingway’s story. The past ten years have been rich indeed, but at the current moment, the muse is leading me in an entirely different direction.

What does writing look like for you? A long session? Short bursts? Every day? Word count?

When I’m asked how many hours a day I spend writing, I often say “As many hours as I have.” Which is sort of a joke about being a workaholic, but also a pretty fair representation of my workaround for life’s invariable busyness. Ideally, I prefer to have at least three or four unbroken hours. It takes time to sink into the place where writing is really made, when my rational, highly distractible and way-too-busy mind takes a backseat, and the story takes over. I also like to see a thousand words on a perfect day—but there are so few of those, wouldn’t you agree? If all I can squeeze in is an hour before a school concert or even half an hour on a regional flight, I will take it—since anything is better than nothing. I can at least make contact, to “touch” this thing I’m making and invested in, like watering a seed, or feeding your sourdough starter so it doesn’t languish like gray matter in the fridge! For me, being precious or rigid about having things be just so would cancel out a LOT of opportunities to write. The devotion is what matters. The practice. The love.

What inspired you to write Circling the Sun?

Beryl Markham was a wonderful accident as a subject. After the publication of The Paris Wife in 2011, I began working on another historical novel, but it just wouldn’t come together. For whatever reason, I couldn’t find the voice or heart of the book. I couldn’t make it sing. During that time—this would have been spring of 2013, I went on vacation to Orlando with my sister and soon-to-be-brother-in-law. He’s a doctor and a pilot, and as we were poolside that weekend, he kept looking up from the book he’d brought along, and saying, “You have got to read about this woman. She’s amazing.” That book was Beryl Markham’s 1942 memoir, West With the Night, but I was far too busy being miserable with the other project to listen. I also thought that whatever mysterious force activates *inspiration* in the universe, it wasn’t likely going to come through my brother-in-law, in Orlando no less! Reluctantly, I took the book home and stashed it on a shelf in my dining room, where it gathered dust for another year and a half before I picked it up. When I finally did, I had an instantaneous and almost visceral reaction to her voice and story: a combination of toughness and fearlessness laced with nostalgia and regret. She was such an adventurer, and accomplished all these incredible things women in her era simply didn’t dare …like a character from a Hemingway story, but she actually lived! I couldn’t help wondering though: how did she get to be who she was…this bold, impossibly original woman who could tackle dangerous feats without blinking? How does the world MAKE someone like Beryl Markham? That’s what really fueled the book.

Why did you make the shift from historical fiction to suspense with When the Stars Go Dark?

My latest book, WHEN THE STARS GO DARK (2021), which will be out next month on April 13, is a suspense novel rather than historical, and yet this fascination with real-life crept in anyway. When I was steeping myself in research, I was eerily surprised to learn that there were a string of abductions of young women in the same time period (1993) and geographical area (Northern California) as my novel – most notably 12-year old Polly Klaas, who was kidnapped at knifepoint from her bedroom in Petaluma during a slumber party while her two best friends watched. It became one of the largest and most publicized manhunts in California’s history, and yet more often such disappearances aren’t national news; many aren’t even reported. I wanted to write about that—about how everyone wants—and needs—to be looked for. And as I did so, many of my own early difficult experiences as a kid growing up in foster care sifted into my story, as did my ongoing fascination with intimate violence, trauma and healing, and the complex, magnetic relationship between predators and their victims. There is real life, and then there is real life. Our human story, which will always, always call to me.

I have a novel idea about a real woman though there aren’t letters like Hadley’s that have kept her voice alive. Her pain, resilience and grace have really drawn me to her. Could you have written Hadley’s story and from her POV without her letters?

When I learned I could access Hadley and Ernest’s letters in the Hemingway Archive, it was a huge boost to my confidence in the book—and my ability to manifest my characters’ voices and selves. Hadley was a terrific letter writer. Her personality came through in her speech rhythms and charming turns of phrase. Her effervescence. And yet, I did not have permission to use any of her wonderful phrases and found that nearly all of the letters were from their 11-month courtship, which occupies only a few chapters of my novel. For the core of my story—once the Hemingways arrived in Paris, and cracks began to form in their marriage—I had very little to go on archivally. And even less from the time when the couple were truly in crisis—once Hadley learns she’s been betrayed. I invented what I couldn’t know: every interior thought, their dialogue, full scenes I created whole cloth. But that’s what writers do. Voice—real or imagined—however crucial a key, never fully unlocks the door to character. You still must sit quietly in the dark and project your way toward them using every tool: intelligence, empathy, curiosity, imagination. Everything you know about why people behave the way they do. What we’re really talking about is earned intimacy. You may suffer a little getting there and fail a little too. But you say your subject’s pain, resilience and grace drew you towards her story. This means you have something important to say about those things based on first-hand knowledge. Grab that and use it as a flashlight as you move deeper into the shadowy terrain of your story, into those spaces you can’t know, not in any rational, quantitative way, but can absolutely find. Go looking for her—I dare you!—and please keep me posted.

I am always interested in hearing about structure. Is it hard for you to come up with? How do you go about deciding on it?

Yes! Structure is something I wrestle with on the daily, because I want what you want, what we all want—to shape and pace my story in the most engaging and effective way possible. One of the most striking and clarifying things I’ve read recently is Kathryn Schultz’s essay “The Secrets of Suspense” in last May’s New Yorker, which asserts—and I totally agree—that “outside of phone books and instruction manuals, it’s almost impossible to find a written work that doesn’t make use of suspense to captivate readers.” If you can’t keep a reader wanting to know what happens next, everything else, no matter how profound or beautifully crafted, is beside the point. Shultz goes on to say that the most essential part of the bomb is the timer, “Counting from one to ten is boring, because what happens next is eleven. But counting from ten to one is gripping, because what happens next is: BOOM!” Doesn’t this say everything? And note, the bomb need not be literal to be explosive/destructive/threatening, as long as we know it’s ticking, and we care about the people in harm’s way. In the prologue of The Paris Wife, for instance, an older, wiser Hadley reports to us from beyond the emotional battlefield. We know her marriage to Ernest has been gutted, but not how or when. “This isn’t a detective story—not hardly,” she tells us. “I don’t want to say ‘Keep watch for the girl who will come along and ruin everything, but she’s coming anyway, set on her course in a gorgeous chipmunk coat and fine shoes…” When the page turns, chapter one finds them at their first meeting at a party in Chicago in 1920. Hadley is playing a Rachmaninoff tune when a dashing 20-year-old Hemingway comes to sit beside her on the piano bench. Tick, tick, tick.

There’s so much more to say about structure—and so, I’ve decided to make this a two-part answer. Stay tuned for more soon, and thanks for sending your questions along. I love talking and thinking about this stuff, and I have an inkling that there are more than a few of you out there who do as well 🙂

Advice and Recommendations

Do you think an MFA is worth getting?

For those of you unfamiliar with the term, an MFA is an advanced degree in the fine arts, and in this case, creative writing. I embarked on mine at the University of Michigan in the mid 1990’s, a spectacularly risky decision for a couple of reasons. I had to borrow the entire tuition in student loans, plus money to live on—some thirty-thousand dollars. I was also the divorced single parent of a two-year-old. And I was getting a degree in poetry, hardly the fastest way to get rich and famous! I’d planned to apply for teaching jobs after, but of course there were no guarantees I’d find one, or that my degree would help me finish a publishable book, or of anything really. The only thing that was certain was that I would have two years to focus entirely on my work and on literature, and that for that time I would be in a community of writers and teachers of writing. I took the leap and have never regretted it. But the artist’s life is one leap of faith after another, I’m afraid to tell you. For years and years after I graduated, I struggled professionally and financially, living paycheck to paycheck, waiting tables well into my thirties so I could save my days for my work. I doubted myself at so many turns, felt crazy and irresponsible. The risk paid off eventually, but that it would pay off was never all that likely. None of us gets a crystal ball, unfortunately, that will tell us everything’s going to be okay, or how each choice fits into the design of our lives. But I can say this. When you bet on yourself, on what you know you must do in order to feel in line with your purpose and whole, you won’t be wasting time or money, no matter what happens next.

Best advice for brand new authors considering writing a memoir? Where do you even start?

When I began writing my memoir, LIKE FAMILY (2003), twenty years ago now (gulp!), I’d never written anything but poetry. Though I was intimidated for sure, I decided that maybe it was okay for me to be a novice, and to learn as I went — from the masters of the craft. I started reading lots of different kinds of memoirs and kept the best of these at my desk as I wrote. I also decided that it was okay to not know where I was going—where the beginning was, or what the end might be. I plunged into a scene, any scene that was super sharp in my memory — available to me—and wrote it through as I would a story, but with myself as the main character, focusing on sensory detail, sense of place, dialogue — all the critical elements of storytelling. Tiny deadlines helped. I made myself write two pages a day and then I printed them out, turning the printed pages upside down in a drawer. Somewhere along the way, nearly two years later, I had what might be called a book, fledgling and rough. But there.

Good luck to you. I hope you’ll find your way. Oh, and one last thought, and a benediction of sorts. May you fully own your story and believe you have every right to tell it💗

Here are a few recs for you!

Do you have any recommended books for aspiring writers to hone their craft?

I love this question and have so many recommendations so I’ll answer it in multiple posts over the next few months (with other questions answered in between!). But to start, I’ll suggest a book I mentioned in my recent newsletter. It’s called IF YOU WANT TO WRITE: A BOOK ABOUT ART, INDEPENDENCE, & SPIRIT by Brenda Ueland (1938). Ueland is one of my creative muses. She was born in Minneapolis on October 24, 1891, and was a journalist, editor, and freelance writer devoted to promoting the creative spirit in herself and others. She lived by two rules, to tell the truth, and to not do anything she didn’t want to. This isn’t a handbook on nitty-gritty grammatical advice – it’s a spiritual guide and if you’re anything like me, as you read it you’ll feel something move deep within.

Here’re some lines I love:

“When Van Gogh was a young man in his early twenties, he was in London studying to be a clergyman. He had no thought of being an artist at all. He sat in his cheap little room writing a letter to his younger brother in Holland, whom he loved very much. He looked out his window at a watery twilight, a thin lamppost, a star, and he said in his letter something like this: ‘It is so beautiful I must show you how it looks.’ And then on his cheap ruled note paper, he made the most beautiful, tender, little drawing of it.

…the moment I read Van Gogh’s letter I knew what art was, and the creative impulse. It is a feeling of love and enthusiasm for something, and in a direct, simple, passionate and true way, you try to show this beauty in things to others, by drawing it. And Van Gogh’s little drawing on the cheap note paper was a work of art because he loved the sky and the frail lamppost against it so seriously that he made the drawing with the most exquisite conscientiousness and care.

Looking back, what advice would you give yourself as an early-career writer?

When I began writing my memoir, LIKE FAMILY (2003), twenty years ago now (gulp!), I’d never written anything but poetry. Though I was intimidated for sure, I decided that maybe it was okay for me to be a novice, and to learn as I went — from the masters of the craft. I started reading lots of different kinds of memoirs and kept the best of these at my desk as I wrote. I also decided that it was okay to not know where I was going—where the beginning was, or what the end might be. I plunged into a scene, any scene that was super sharp in my memory — available to me—and wrote it through as I would a story, but with myself as the main character, focusing on sensory detail, sense of place, dialogue — all the critical elements of storytelling. Tiny deadlines helped. I made myself write two pages a day and then I printed them out, turning the printed pages upside down in a drawer. Somewhere along the way, nearly two years later, I had what might be called a book, fledgling and rough. But there.

Good luck to you. I hope you’ll find your way. Oh, and one last thought, and a benediction of sorts. May you fully own your story and believe you have every right to tell it💗

Here are a few recs for you!

I would love to know how you stay invested in the process?

A friend who is a budding novelist and memoirist asked me this same question recently—followed by a nervous laugh. How many hours? More than there are numbers for. The time at the desk and the time in the carpool lane, picking up my son from school, still thinking about the scene I’ve just left open on my laptop. The writing I do when I’m dreaming, where the scene is somehow still—and always—open. This latest novel began as an idea four years ago. Once I started writing, I wrote seven full drafts and countless smaller revisions. Millions of words. Ten- and twelve- and fourteen-hour days sometimes, passing in a blur. How do I stay invested? All I know is that every time I see what else needs to be done, I can’t help but roll up my sleeves and do it. Because I made it, and it’s my responsibility to give this book everything, to see it through to its final form. What happens then is up to the gods. I can’t foresee or control a book’s fate in the larger world, but I can do this. Writing is my one vice, I like to joke, my obsession—but in truth I would never work this hard for any other reason but love ❤️

Any advice on when it’s time to pack up a novel and move on to a new project? Or what to do when feeling stuck with a project?

Oy, that’s a tough one, I’m not gonna lie. Years ago, after publishing The Paris Wife, I signed a contract to write a novel about Marie Curie. I was really passionate about the story, but for some reason, I never found the voice. Even after three years, multiple drafts and 100 percent of my effort—ass in the chair, working every day—I never felt the heartbeat. To complicate matters, my agent had just delivered her son prematurely, and clearly couldn’t help me. My editor told me the pages left her cold. In the midst of that stalemate, which felt awful, I happened to read a short passage of Beryl Markham’s memoir, West with the Night, and felt an immediate and undeniable lighting strike. For several months, without telling anyone what I was doing, I wrote like crazy. The words came pouring out, almost as if all of my frustration with the other book had created a dam that needed to break somehow. The new writing also had a tinge of the illicit. I was cheating on Marie Curie with Beryl Markham! (Talk about an interesting love triangle.) As difficult as it was to leave years of work in the drawer, I had to move where the energy was. The first draft of Circling the Sun took 5 months—the fastest I’ve ever written by far. As for Marie, though I couldn’t have known it, we weren’t finished with each other. In 2020, eight years after I put her in the drawer, an editor with Audible Originals reached out to see if I had any ideas for a novella-length story. Did I? Somehow, the change in form helped me crack the code. All of which to say, I can’t tell you what the “right” thing to do is. But nothing is ever wasted. That I know for sure. And if you do put down this book—similarly—to follow the energy elsewhere, one day you might open the drawer again, and find your current pages still glowing faintly, like radium.

Are writing retreats worthwhile? Which ones are especially helpful for a writer of historical fiction?

First of all, I have to shout an unqualified YES about the value of writing retreats and workshops for writers of any genre, at any level. With each writing retreat I’ve been part of, whether as a teacher or a student, I’ve always come away with far more than I anticipated, whether that be fresh ideas and inspiration, a new perspective, a new friendship, or simply a rich reminder of why writing matters to me, and matters in a larger sense. The majority of my most cherished writing friends I met in retreats and workshops like the Kaua’i Writer’s Retreat/Conference. They’ve helped me grow as a writer, reader, and teacher, and have also become my confidants and my soundboards, the people I call when I have good news to share, or need to be talked off the ledge. Ultimately, we gather to widen the circle, to learn and share, and to feel a part of something larger than ourselves. Prioritizing the time to focus on your work can be incredibly important in and of itself, symbolic of your intention, and your devotion. There’s a poem by Martha Postlethwaite that speaks to this idea for me: “Do not try to save/the whole world/ or do anything grandiose. /Instead, create a clearing/in the dense forest/of your life/and wait there.”

As for where to begin looking, I like Poets & Writers as a resource.

https://www.pw.org/content/twentytwo_of_the_most_inspiring_writers_retreats_in_the_country.

Think about your goals for the retreat, and what your schedule permits. Decide if a workshop or conference meets your needs, or something more like a retreat or residency. Go to websites and read endorsements and reviews to sharpen your focus, as well as the bios of writing instructors or past participants. As for your question about historical fiction, I don’t think zooming in on any particular genre matters as much as the quality of the retreat. If anything, opening your exposure to a variety of other styles and subject matters can help spark freshness rather than be a detriment. When I was working on The Paris Wife, I surrounded myself with writing I admired, but chose not to read much historical fiction, because I didn’t want to see or feel those fence-lines in my line of sight, but rather to make something new.

Some of the retreats I can vouch for personally or through recommendations from close contacts include: Kaua’i Writers Conference, Foreword Retreats, Sirenland, Aspen Summer Words, The MacDowell Colony, Ucross Foundation, Vermont Studio Center, Ragdale, Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, Yaddo, Hedgebrook, but honestly the list goes on and on. I hope you make that clearing in the forest, and find something wonderful for you and your work.

When you’re done with a first draft, how do you return to it? To pick it up and then start working on the revisions? Do you have fears/worries? How do you push past that?

It’s totally natural and oh-so-human to worry that a first draft, completed and confronted, won’t come close to matching the book in your mind. How could it? There, it can be what you intended, but on the page, it can only ever be what you’ve done so far. The process can be exhausting and a little demoralizing. Like reaching the end of a marathon only to find there’s another one stretching on and on just past the finish line.

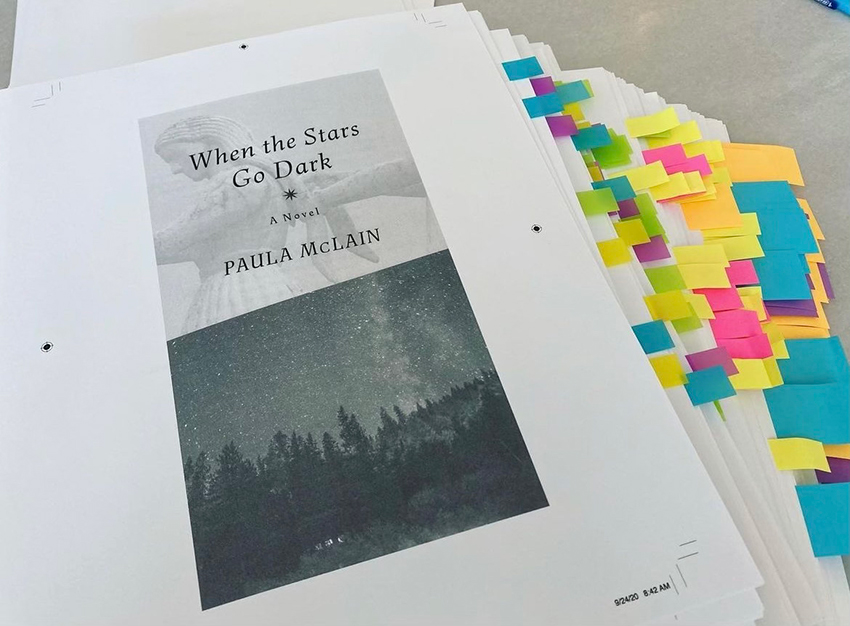

First of all, make sure you celebrate each stage for the accomplishment it is, and feel good about and grateful for the energy and determination that got you there. If you’re overly critical right away, you’ll just want to rip it apart. Try to just read it with an open mind and some distance or freshness. I find it helps to print out and read it in manageable chunks while making notes on flags, in the margins, or right on the page. Then, be committed to meeting your draft in a clear-eyed way, really looking at what you’ve done so that you can deepen it. When I dive back in, I usually don’t start at the beginning, and I definitely don’t start with the hardest task or fix. I’m trying to find confidence and momentum, to follow the energy and then use it to ride over the more challenging bits ahead.

I like to think of the process as a palimpsest—built layer by layer, thread by thread, deepening, refining, and growing. Stretching. Zebra and giraffe babies find their feet within 24-48 hours because they have to be able to outrun predators on the savannah. But book babies—at least my book babies—are more marsupial, needing time in the pouch to fully develop. Doesn’t every new thing deserve a little tending to and encouragement? If I think of this stage as part of my responsibility—the carrying and nurturing, the patience and time—then maybe when it’s finally ready to walk, it will fly.

Miscellaneous

Do you ever go back to the coffee shop where you wrote The Paris Wife to write other stories? Or was it a moment in time that took you to Paris and Paris alone?

I love this question! Actually, I have returned to that Starbucks from time to time to write other things, but only in a passing way, to “visit,” rather than to dig in again. I’m very nostalgic, and feel protective of the place, I suppose, and of that period in my life, when the same brown velveteen chair I sat in every day became my version of the Tardis. My children sometimes joke that there should be a plaque above that chair with my name on it, the way The Elephant House Café in Edinburgh pays homage to JK Rowling. I’ve always laughed at that, reminding them that Harry Potter is several hundred tiers above The Paris Wife in the realm of literary phenomena. And yet. Two years ago, we took a family trip to Scotland, and stopped by The Elephant House one rainy (of course!) Edinburgh afternoon for tea and cake. I expected the framed photos of Rowling and news clippings of interviews she’s given about the importance of the place in the origin story of the book and her career. I expected tourists (like me) taking selfies outside of the vibrant orange façade of the building. Then I went into the ladies’ room and was completely blown away to discover that every square inch of every wall was covered several times over with thank you notes and love notes to Rowling, emotional outpourings about the unbelievable importance of this thing. This BOOK. That’s when I began to cry. How incredible that stories can have such power—to move and inspire us. To change our lives. The truth is, I will never have a plaque over that brown chair in Starbucks, because the chair is gone. The whole place has had a clean, modern refresh and looks nothing like it did in 2008, when I wrote there. But of course, the chair was never really the time machine that swept me away. Was it?

Is your desk really that neat?

First of all, I adore this question. It was posed way back when I first began this #askmeanything series and posted a photo of my “neat” desk. (Swipe to see that photo.) We put so much effort into appearing spotless for one another, but of course that’s not real life. Or not MY real life in any case! So here is my actual desk on an average day, complete with my breakfast in the foreground, plus wadded up tea bags, spent-but-not-tossed-out pens, Tic-Tacs, post-flags, three pairs of glasses, notebooks, poetry, research, favorite books, a Himalayan salt lamp (for the positive ions, of course 🌀) and various talismans. Like the Georgia O’Keeffe postcard a dear friend sent me a decade ago when I thought I was writing a novel about O’Keeffe, with a faded message on the back that says, “She’s waiting for you.” And the milky, green and white stone I found in Iona, Scotland, on a sacred beach. And THE SUN tarot card. 🌞And a letterpress card with my favorite Mary Oliver poem, “Wild Geese,” sent to me for my birthday by my agent Julie Barer and editor Susanna Porter. What are your talismans? Those things you keep around you as you read and think and write and “make,” which you wouldn’t want to be without?

And ask any questions you’d like for me to answer in future posts. This month I’m particularly interested in talking about THE PARIS WIFE (2011) in honor of its tenth anniversary, so I’d especially love to hear your questions related to that ❣️

What is your workspace like?

I can’t tell you how much I loved the deluge of practical questions that followed my last Ask Me post, showcasing my new desk/work space. Because these things matter. If I’m going to spend 5-7 hours a day at my desk, I want to like that desk. This one I love, and spent a lot of time looking for / wanting a work table more than a desk. It’s called the Phoenix rustic table from Crate and Barrel, made by hand in a small factory in Puebla, from reclaimed Brazilian telephone poles. If you need drawers or a super smooth surface, this won’t be your jam. It’s coated with beeswax, so not rough to the touch, but not super smooth either. I love the knotholes, and never worry about rings from my coffee cup! As for my setup, I followed a suggestion from a physical therapist to keep neck and shoulder tension more or less controllable. Apparently having your screen about 18 inches away, and at eye level is most ergonomically sound, and kindest to your eyes and body. The ladder to my left is super light and actually for blankets, but I had a brainstorm one day thinking it would be great for tented books—which I usually leave lying around everywhere. A few of these titles I’m currently dipping in and out of, others are reference books I like having at my fingertips. Others, like the Walter Benjamin, fit better here than on my bookshelf, freeing up precious space. Thanks for the questions, and happy writing!

Do you dream about your characters?

I do! The most surprising example is when I dreamed about Martha Gellhorn before I wrote about her. Though I’d long been aware of Martha as Hemingway’s third wife, I never considered tackling her as a subject until the dream got my wheels turning. It felt like a sign. Like a message from my subconscious mind to take a deeper look at her. I love how rich dreams can be, and how creative. The best dream I’ve ever had about a character was when I dreamed of Hemingway when I was deep into working on The Paris Wife (2011). In the dream, he walked up to me—the older “Papa” Hemingway, not the young man he was in my novel—and said, “I like you. You’re a person.”

“Well thanks,” I said. “I like you too.”

“Sometimes I feel like I’m a hundred years old,” he responded.

And I said, “That’s how you know you’re a person.”

When I woke up, I had the loveliest sense of the dream being a blessing, a benediction. Like a big wet kiss from the universe that diving into this story was a rich way to be spending my time and energy. That I was on the right track.

Do you dream about your characters? Either those you’ve written, or those from books you love? If so, I’d love to hear about it!